Numerical methods#

There is no shortage in the literature for methods to solve the equations outlined above. The methods used by ASPECT use the following, interconnected set of strategies in the implementation of numerical algorithms:

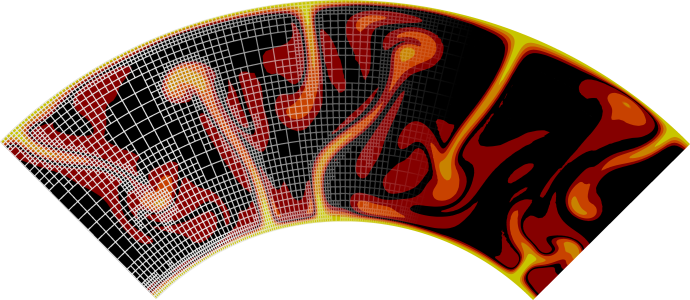

Mesh adaptation: Mantle convection problems are characterized by widely disparate length scales (from plate boundaries on the order of kilometers or even smaller, to the scale of the entire Earth). Uniform meshes can not resolve the smallest length scale without an intractable number of unknowns. Fully adaptive meshes allow resolving local features of the flow field without the need to refine the mesh globally. Since the location of plumes that require high resolution change and move with time, meshes also need to be adapted every few time steps.

Accurate discretizations: The equations upon which most models for the Earth’s mantle are based have a number of intricacies that make the choice of discretization non-trivial. In particular, the finite elements chosen for velocity and pressure need to satisfy the usual compatibility condition for saddle point problems. This can be worked around using pressure stabilization schemes for low-order discretizations, but high-order methods can yield better accuracy with fewer unknowns and offer more reliability. Equally important is the choice of a stabilization method for the highly advection-dominated temperature equation. ASPECT uses a nonlinear artificial diffusion method for the latter.

Efficient linear solvers: The major obstacle in solving the system of linear equations that results from discretization is the saddle-point nature of the Stokes equations. Simple linear solvers and preconditioners can not efficiently solve this system in the presence of strong heterogeneities or when the size of the system becomes very large. ASPECT uses an efficient solution strategy based on a block triangular preconditioner utilizing an algebraic multigrid that provides optimal complexity even up to problems with hundreds of millions of unknowns.

Parallelization of all of the steps above: Global mantle convection problems frequently require extremely large numbers of unknowns for adequate resolution in three dimensional simulations. The only realistic way to solve such problems lies in parallelizing computations over hundreds or thousands of processors. This is made more complicated by the use of dynamically changing meshes, and it needs to take into account that we want to retain the optimal complexity of linear solvers and all other operations in the program.

Modularity of the code: A code that implements all of these methods from scratch will be unwieldy, unreadable and unusable as a community resource. To avoid this, we build our implementation on widely used and well tested libraries that can provide researchers interested in extending it with the support of a large user community. Specifically, we use the deal.II library ([Bangerth et al., 2007, Bangerth et al., 2012]) for meshes, finite elements and everything discretization related; the Trilinos library ([Heroux et al., 2005, Heroux and others, 2011]) for scalable and parallel linear algebra; and p4est ([Burstedde et al., 2011]) for distributed, adaptive meshes. As a consequence, our code is freed of the mundane tasks of defining finite element shape functions or dealing with the data structures of linear algebra, can focus on the high-level description of what is supposed to happen, and remains relatively compact. The code will also automatically benefit from improvements to the underlying libraries with their much larger development communities. ASPECT is extensively documented to enable other researchers to understand, test, use, and extend it.

Rather than detailing the various techniques upon which ASPECT is built, we refer to Kronbichler et al. [2012] and Heister et al. [2017] that give a detailed description and rationale for the various building blocks.